There are many people searching online for information that compares Western martial arts to Eastern martial arts. This article has been written to help answer many common questions with a comprehensive and holistic approach.

What is meant by ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’?

Broadly the term ‘Western martial arts’ can apply to any martial art whose origins come from cultures that lived or live in the western hemisphere of the globe.

The popular approach to history and culture has been to divide the world’s globe into ‘Eastern hemisphere’ (or ‘Eastern world’ and ‘Western hemisphere’ (or ‘Western world’) to make subjects such as history more dissect-able, although this approach can often lead to misunderstandings that cultures in the Western hemisphere were isolated from those in the Eastern hemisphere. In reality for the majority of recorded human history there has been extensive trade routes connecting Eastern cultures to those in Europe.

‘Eastern’ and ‘western’ in the contemporary sense of the word mean which countries sit to the east or west of the prime meridian, which is an arbitrary line used in geo-navigation systems, although when reading historical accounts that discuss “West” and “East” we must consider that what is meant by the “prime meridian” has changed in precise positioning over the centuries, so this usage may not always be consistent, either.

More specific to the usage by the modern martial arts community, when the term ‘Western martial arts’ is used broadly it can refer to any martial arts whose origins stem from a culture that has existed in the the historical boundaries of the Greco-Roman world in the classical antiquities period, to the American continents, with “Europe” often defined more broadly as any territory that is dominated by a Western superpower such as the United Kingdoms so this means countries like Australia are often considered part of the “Western world” too.

In comparison ‘Eastern martial arts’ are those considered to be part of Asia and island cultures of the Pacific ocean, but it can also include near east cultures such as Egypt and Babylonia.

The takeaway here is that what is defined as ‘Western’ and what is defined as ‘Eastern’ is not always agreed upon because the terms are misnomers with not necessarily specific definitions.

As a consequence of these terms being so broad it is more common for martial arts historians to refer to specific cultures when discussing the topic instead of trying to lump potentially hundreds of different cultures under one uncomfortable label.

How does the term ‘Western martial arts’ relate to HEMA?

In the early days of the reconstruction of Historical European martial arts it was common to use the term ‘Western martial arts’ when referring specifically to historical European martial arts, but as ‘Western’ is a misnomer with a wide variable of definitions this term is typically not used anymore and most individuals instead use the term ‘HEMA’ to be specific to avoid confusion and create clear distinction between more modern sport martial arts such as boxing and sport Olympic fencing, as well as martial arts of indigenous peoples to the Americas which survive today in fragmented oral traditions. Technically speaking Brazilian jiu-jitsu can be considered a western martial art, too.

So it isn’t that ‘western martial arts’ is a bad or inaccurate term for historical European fighting styles, but rather that the term is often so broad that it can be confusing to refer to specifically European martial arts as ‘western martial arts’. In effort to provide more clarity the term ‘HEMA’ has been created as an acronym for Historical European martial arts, as it a mouthful of a label.

The relationship between HEMA and Eastern martial arts

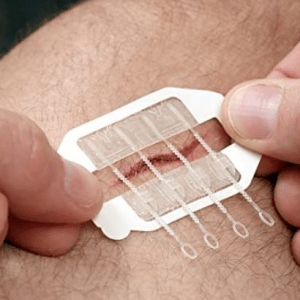

One of the most significant differences is that the European arts practiced by HEMA martial artists have been recreated over the past thirty years based on a combination of studying the source manuscripts, and injection of what is referred to as ‘frog DNA’ (in reference to the film Jurassic Park), a term used in this sense to mean concepts that are borrowed from other martial arts — including some Asian arts. For example the test cutting practice used in HEMA is non-historical to Europe and is taken instead from contemporary Japanese sword art practice of tameshigiri (the popular form of which today is, notably, not a historical Japanese martial art practice, either) .

The reason that elements have been borrowed from other martial arts is largely because the majority of Historical European martial artists practice styles of combat that have no living lineages of direct transmission of knowledge from master to student and the source material that serves as the only record these martial arts ever existed are not wholly instructive of what they mean, with often key details such as specifics of footwork missing from the material.

By contrast the majority of Asian martial arts practiced today come from a living lineage of masters that can date back at least a century and were themselves shaped by some kind of older tradition, although even among these lineages many of the Asian martial arts have dramatically transformed from their more ancient incarnations (Japanese Kendo is an example of this).

There is often a popular belief that the the styles of Asian martial arts practiced today possess an unbroken line of transmission from teacher to student and that historical Asian martial arts never died off the way that historical European martial art traditions did. This is a misconception and as we later discuss you’ll come to understand the reasons why this is typically not the case.

How do Historical European martial arts compare to Eastern martial arts?

This is an enormous question that has no simple answer because what is meant by ‘Eastern’ covers hundreds of different cultures, many of which are quite different from one another.

Therefore as the label ‘Eastern’ is as equally broad as ‘Western’ we will try to be a little more focused in answering this question.

Chinese martial arts

We have to first define what is meant by ‘China’ as for most of history the term ‘China’ has been applied broadly. The terms ‘China’ and ‘Chinese’ are not historically used by what today are considered ‘Chinese peoples’; the term ‘China’ originates as a loan-word from Sanskrit that was spread by Portuguese traders in the 16th century.

In ancient times the martial arts of what is today considered ‘China’ were heavily influenced by importation of martial traditions from India and further shaped by periods of warfare from both within and outside of the broad territory lines of Chinese cultures. Historically China has been a collection of independent states who often fought against each other for control of territory, with the most extensive of this fighting taking place in the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods. This combat ended in 221 BCE when the state of Quin conquered the others and established the first empire. Over the centuries this empire crumbled and was replaced by varying periods of warfare of several splinter states until the Mongol conquest of these Chinese states in the 13th century, which itself became toppled and replaced by the Ming dynasty in 1368. After a few more uprisings and toppling of dynasties, China eventually became controlled by its current Communist state, The People’s Republic of China.

The history of China is consequently a very long and complex subject to study and so examining its martial arts is often obscured by this fog.

Generally speaking in contemporary times Chinese martial arts are a heavily diluted version of their original historical counterparts due to reforms made during and after the Cultural Revolution socio-political movement that lasted from 1966 to the death of Mao Zedong in 1976. During this period militant efforts to purge “traditional Chinese” culture to reinforce Mao’s control over the country as a dictatorship resulted in widespread massacre of cultural teachers and destruction of centers of traditional culture, including the burning of many religious temples and their records. While often overlooked by martial artists today the Cultural Revolution was a significant event that led to roughly 3 million individuals to be killed specifically because they were well known teachers of traditional Chinese culture, and this included well known martial art masters. And even prior to the Cultural Revolution there was the “Great Leap Forward” that devastated the population, leading estimates of somewhere around 45 million people to die of starvation. In total it is estimated around 80 million Chinese people died during Mao’s reign over China.

What survives today as ‘Chinese martial arts’ is a fragment of what once existed before these two major events, with lots of charlatans today taking advantage of the destruction of records and lineages to claim themselves to be heirs of secret knowledge and ancient traditions.

It can surprise people to learn that the current form of the Shaolin Temple is heavily shaped by Communist party reforms taking place after Mao’s death, that during the Cultural Revolution the monks were heavily persecuted, and that by the time Mao died there was only a handful of monks remaining, and a non-functioning religious sect by the 1980s. Even before Mao’s reign of terror the Shaolin temple had previously been looted and destroyed as a consequence of the anti-Buddhist policy pursued by the Republican Government forces in 1928. A fire was set to the temple, destroying most of the buildings. Many of Shaolin’s most precious relics were looted, its massive library of religious and martial arts treatises lost forever.

It would not be until the 1982 film Shaolin Temple starring Jet Li became a box office smash success that the Chinese government took interest in utilizing Shaolin for propaganda purposes, as well as developing a lucrative revenue stream based on tourism of cultural sites. Despite propaganda claims to the contrary there were no longer any Shaolin monks remaining at the temple by the time Shaolin Temple filmed in 1982. When the Chinese government created Shaolin demo teams to tour the world in the 1990s they recruited Wushu artists to assemble the teams and dressed them in Shaolin robes. The version of Shaolin monastery that exists today is a reconstruction that is controlled directly by Chinese government officials and the abbot is a figurehead. It also teaches contemporary sport Wushu instead of more historical Shaolin forms although this fact is often obscured in Chinese propaganda related to the temple.

As a consequence of the Cultural Revolution the vast majority of “traditional Chinese martial arts” practiced today are in actuality relatively modern martial arts whose historical origins tend to be rather dubious when trying to claim lineages older than a century. Contemporary sport Wushu is the predominant form of Chinese martial arts today, which developed out of government standardization of Chinese martial art practices for sport usage which started in 1958 and is heavily influenced by the acrobatic stage fighting of Chinese Peking theater. Wushu has little in common with historical martial arts practiced by Chinese people for warfare. This is why Wushu is ineffective in combat sporting events such as mixed martial art matches or even kickboxing tournaments. However due partly to the success of exporting Wushu in popular media such as movies and partly due to efforts by the Chinese government to censor discussion about the Cultural Revolution the fact that modern “kung fu” is not very ancient goes largely unnoticed by the general population. This is relevant to the comparison to HEMA, as the goal of HEMA is to recreate the martial arts as they were practiced by historical European fencers.

(You can read more about this topic in the book Possible Origins: A Cultural History of Chinese Martial Arts, Theater and Religion by Scott Park Phillips and the book Politics and Identity in Chinese Martial Arts by Lu Zhouxiang)

As for contemporary Sanshou the practice is almost wholly adopted from Russian Sambo (which itself is an eclectic art developed in the 1920s combining catch wrestling, Judo, and Turkic wrestling styles) as part of Communist ties between the USSR and China.

This is not to say that Chinese martial arts entirely died out; many teachers fled the mainland to places such as Hong Kong and Taiwan, and took their traditions with them — Bruce Lee’s famous teacher Ip Man is an example of one of these teachers– but many lineages such as Manchurian style archery were completely wiped out by the consequences of the Cultural Revolution. Even among those martial artists who escaped the purge it does not necessarily mean they fully inherited their traditions; as an example with Ip Man he had only trained for a few years with his master, Chan Wah-shun, from the time he was 9 years old to when Chan died; Ip Man was still only thirteen years old at this time. In turn his master Chan Wah-shun himself had only studied martial arts for four years under his master, Leung Jan. It is unlikely a full transmission of the art was passed down.

Lastly we must mention Tai Chi Chuan briefly as it is one of the most widely practiced Chinese arts in the world. Also romanized as Tàijí quán or Taijiquan, this martial art has several sub-traditions or schools within it. The art is attributed to having developed in the Wudang Mountains, a location of cultural significance for Taoism (Daoism) and martial arts. The history of Taoism is intertwined with many myths and legends pertaining to mysticism and to fully discuss this topic in detail would require another essay. The short version is that Tai Chi Chuan has its roots in the martial traditions of Chen clan from Chenjiagou practiced sometime in the 1800s and that Yang Luchan became an initiate of these traditions sometime in the last half of the 19th century, with many legends attributed to him. As with other aspects of traditional Chinese culture Tai Chi Chuan it was suppressed during the Cultural Revolution. During the 1980s Tai Chi spread internationally and seeing this interest the Chinese government developed the Wudang mountain villages into tourist destinations and the legends associated with Tai Chi became part of considerable marketing efforts to attract foreign tourists, with the martial art now adopted to conform to the framework that had been developed for contemporary Wushu. This is popularly believed to have diluted the art of much of its martial applications, and there is currently a lot of controversy surrounding this as notable masters of Tai Chi lose fights to mixed martial art athletes.

The purpose of pointing this out is not to criticize Chinese martial arts but rather this information is necessary to know if one is to accurately compare Historical European martial arts to Chinese martial arts. The reality is most historical Chinese martial arts are no longer practiced and have been replaced by contemporary styles that have been heavily influenced by the acrobatic stage fighting of the Chinese theater, and those which do have lineages pre-dating the Cultural Revolution may not be full inheritances of the arts, missing substantial portions of their original curriculum.

Considering all of this information the majority of Chinese martial arts today possess very little martial value and are primarily a form of sport exercise focused around solo form practices and drilling. Tournaments featuring weapons sparring between contestants are virtually unheard of, and among those who practice bladed weapon forms they tend to use blades that are much lighter and more flexible than their historical counterparts; as an example the historical Jian sword is a fairly firm blade using differential hardening techniques and is compared to the kind of European single-handed double edged swords used in western sword martial arts, but the modern Wushu version of the Jian is far more whip-like, lighter and made of stainless steel.

It is worth mentioning that just as the HEMA movement is focused on the reconstruction of European historical fighting styles there is a small movement of those trying to study and reconstruct more historical Chinese martial arts based on texts that have survived the Cultural Revolution. The Historical Combat Association of Singapore is one of these groups, operating the ChineseLongsword.com website to distribute manuscripts they have located as source material.

Japanese martial arts

Historical Japanese martial arts were imported originally from Korea, as the Japanese people originate from Korean ancestors. Of course its worth noting that ‘Japan’ is, much like ‘China’, not a historical term used by the Japanese people for themselves, either and much like ‘China’ originates from the word used by 16th century Portuguese sailors to refer to the island nation.

Within their own language the Japanese refer to themselves as Nihonjin and their country as Nihon or Nippon, depending on how you wish to romanize the original characters of their language. They have a rich history, with swords from legend and myth often forming a central part of their early history; as an example their origin myths involve the sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi, which is perhaps of equivalent importance to Japanese mythology as King Arthur’s Excalibur is to English mythology.

As ancient Korean martial arts were heavily influenced by the arts of India and China there are parallels between early Japanese martial traditions and those from the Asian mainland but over the centuries a uniquely Japanese tradition developed that coincided with the development of unique blade smithing techniques such as that used to forge the katana. During the Edo period from 1603 to 1868 there developed thousands of different schools of martial arts teaching varied principles and favoring certain weapons over the other. However during the Meiji Restoration a crackdown on the samurai caste in order for the Emperor’s government to consolidate power and “modernize” the country in line with Western military thought of the period led to a purging of many elements of classical Japanese culture associated with the samurai, including the outlawing of the wearing of swords. This led to a failed series of rebellions culminating in the Satsuma Rebellion. This crushing of the samurai extinguished many lines of families and the oral traditions of many of these Edo era schools were lost.

As we discuss in our article about Kendo attempts were further made by the Meiji government to standardize sword fencing for military and police usage in the period leading up to World War II but after the surrender of Japan the American occupation resulted in post-war reforms intended to demilitarize the culture of the Japanese themselves. Martial arts were outlawed for a period of time and when allowed to resume possessed a very different philosophy and were intended to teach little of martial value by design. This important detail is often overlooked by Asian martial artists today however.

Iaido is another contemporary Japanese sword martial art that stems from standardizations made to historical battōjutsu techniques by the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai in the 1930s, with further reforms made in post WWII Japan as part of demilitarization. The sport of Iaido today is a highly ritualized sport.

It is worth mentioning there have been several contemporary attempts to reconstruct older more historical Japanese combat arts which fall under the label of Koryū (“old schools”) but these schools often claim lineages pre-dating the Nippon Butoku Kai reforms and the Meiji Restoration, and in general very little evidence has been provided for the existence of these lineages dating back more than a century. This has not prevented many people from believing the claims made by teachers of these koryū schools though and you will find many koryū apologists on the internet who sincerely believe they practice ancient ninja arts and swordsmanship styles attributed to legendary historical figures that somehow survived intact during the Meiji government crackdown on samurai and the high death toll of Japanese men during World War II.

As far as uniquely Japanese unarmed combat traditions go, Judo and sumo are the two remaining traditions. Sumo is considerably older than Judo but it is virtually unheard of outside of Japan; Judo by comparison spread globally and is the focus of what we’ll discuss.

Around the same time as the Satsuma Rebellion a young man named Kano Jigoro learned Tenjin Shinyo-ryu style jujitsu while attending Tokyo Imperial University from one of the few teachers officially allowed to still teach samurai arts, Fukuda Hachinosuke. Kano would then study several other jiu-jitsu traditions before deciding to revise them into a form that would be suitable to teach publicly in the new political climate. Kano removed any techniques that used striking attacks, weapons and other lethal techniques to develop his own style focused on using momentum to disrupt an opponent’s balance and then throw them to the ground. He called this art Kodokan Judo and it became adopted by the Tokyo police forces, and in 1889 Kano became chair of a committee of the Dai Nippon Butoku Ka to develop tournament rules for jiu-jitsu, and used this relationship with the Dai Nippon Butoku Ka to spread his Judo throughout schools in Japan as well perform demonstrations of it in worldwide events such as the 1932 Olympics.

It is worth mentioning that the rules of early Judo changed quite a’bit over the early years of the art and this resulted in diverging lineages; as an example, rules to restrict emphasis on groundwork fighting were implemented in 1925. Most people today are familiar with “Brazilian jiu-jitsu” and this has its roots in the pre-1925 ruleset that Mitsuyo Maeda taught to the Gracie family in Brazil in 1915 before these rule changes occurred and is why the Gracie splinter from contemporary Judo has more emphasis on groundwork than modern Judo does.

By the time of World War II the Dai Nippon Butokukai had gained virtually total control over the practice of martial arts in Japan, with only their interpretations officially allowed to be taught. The vehicles for this instruction was primarily the public education system, with Judo and Kendo matches taught alongside training in bayonet and grenade throwing.

As with Kendo, Judo was banned during the American occupancy of Japan but restrictions were lifted in 1948 after de-militarization reforms had taken place. Unlike with Kendo, Kano’s art had already diluted most of the historical combat oriented applications of jiu-jitsu long before the American occupancy so the post-war version of Judo was not too different to its pre-war incarnation but competition rule changes in the years after have substantially changed the focus of Judo techniques.

We will also mention Aikido, a martial art founded by Morihei Ueshiba, who based it on Daitō-ryū Jujutsu, another unarmed martial art developed by Takeda Sōkaku during the turbulent years of the Meiji Restoration in response to the sword bans. Daitō-ryū Jujutsu claims to possess a long lineage stretching back to the 12th century but there is no evidence for this. Morihei Ueshiba’s life has a variety of fantastical stories attributed to him and his martial art transformed into a guru cult, likely due to influence from Ueshiba’s involvement with the Oomoto-kyo cult that sprang up in the the last decade of the 1800s. The post World War II version of Aikido teaches a variety of techniques considered to be diluted compared to the pre-war incarnation, and require a complying partner in order to perform. It is popularly considered to serve very little practical usage in a real combat situation.

Various styles of karate are also practiced in Japan but its origins are not Japanese.

Okinawan martial arts

Japan is often associated with karate but karate is more properly considered an Okinawan martial art, and which largely escaped the crackdowns by American forces by virtue of Okinawa having a contentious relationship with Japan to begin with. The Okinawan population was not the focus of the de-militarization efforts that took place post-World War II.

Karate originated as a southern style of Chinese martial art combat that was imported to the island in the 14th century, possibly associated in some way with the styles practiced by the Southern Shaolin temple that is believed to have been destroyed during the 18th century by Quing forces, although precise records of this history are difficult to come by in post-Cultural Revolution China. Over the centuries these Chinese martial arts were imported and practiced under the label of Naha-te, until the development of “Karate-do” by Gichin Funakoshi in 1936, which he advertised in Japan and worldwide. This style is often referred to as Shōtōkan today although that was more properly the name of Funakoshi’s school, and he instead referred to his art as just “karate-do”. Karate borrowed the ranking and uniform of Kano Jigoro’s Judo to help market itself, as well as changing the names of many of the kata to Japanese equivalents to obscure the Chinese origins of the art in order to be approved by the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai to teach karate in Japan.

Another major change which occurred to karate during this time is adoption of a more Western style of training method for instructing large groups of students. Karate also incorporated several techniques from boxing and savate as well.

(It should be noted that due to rules changes and technique innovations in both the sports of savate and boxing over the years since the 19th century that both modern boxing and savate have made substantial adjustments to their techniques. The present day forms of these combat arts are not as similar to their 19th century counterparts, and it is the 19th century versions of these combat sports which were integrated into karate, not the modern versions).

Many US service members would study karate while stationed at the naval bases in Okinawa and bring these arts back with them to the United States. At the same time Japanese and Okinawan immigrants to Hawaii and California also spread karate into the United States, often teaching service men stationed at the bases on Hawaii.

Due to karate’s origins as a Chinese martial art tradition that was not significantly impacted by either the Cultural Revolution nor the post-World War II crackdown on martial arts in Japan, the martial art taught by Gichin Funakoshi may have more in common with historical Chinese martial art practices than many contemporary styles of Chinese martial arts taught in mainland China do.

Korean martial arts

Ancient Korean martial arts are heavily influenced by the martial arts of India and China. In the same pattern of parallels as with Japan and China, the Korean people’s history also involves long periods of independent states warring with one another for territorial dominance. Various martial arts such as Subak and Taekkyon developed during this period. The Mongol invasions led to influences on the martial traditions, with many of their weapons adopted.

Ssireum is a folk grappling tradition with practices dating back to the Goguryeo (Koguryo) period and contemporary sport ssireum has influences from Japanese Sumo likely as a consequence of the Japanese occupation of Korea between 1910 and 1945. During this period of time the Japanese military attempted to govern the territory by suppressing aspects of traditional Korean culture and replacing them with Japanese equivalents, along with the theft and sometimes destruction of historical artifacts. For example the Gyeongbokgung Palace dating back to the Joseon dynasty was completely destroyed and the Japanese General Government Building built on its ruins. The version of the Gyeongbokgung Palace that exists today is a recent reconstruction.

Despite contemporary claims the martial art of Taekkyon is extinct; by the time of the Japanese occupation it had devolved into a folk kicking game played by children. This is well documented in the events that led to the development and misrepresentation of Tae kwon do by the South Korean government as a distinctly Korean version of Taekkyon when in reality Tae kwon do is a modified version of Karate featuring a heavier emphasis on acrobatic kicking techniques inspired by the folk kicking game which Taekkyon had devolved into. For a detailed account of the shenanigans that led to this misrepresentation and the key players in the development of Tae kwon do you can read the book A Killing Art: The Untold History of Tae Kwon Do by Alex Gillis.

During post-Japanese occupation of Korea the South Korean government has engaged in a number of creative efforts to build national unity with attempts to reconstruct lost Korean culture and heritages, as well as to portray itself as the only true representative of the Korean people in contrast to North Korea. The purported existence of Taekkyon surviving to present time is one of these propagandist efforts. There is absolutely no proof for the claims made by Song Deok-Gi of being the last master of Taekkyon and the martial art he taught is completely unsuitable for real combat conditions. The contemporary practice of Taekkyon is also very clearly inspired by karate, albeit in a different way than Tae Kwon Do is.

This also applies to Haidong Gumdo or Kumdo, which purports to be based on historical Korean martial art swordsmanship dating back to the Hamurang, but the art is wholly borrowed from contemporary Japanese sword arts, mostly Iado and Kendo.

Indian martial arts

The history of martial arts in India dates back to antiquity, and heavily influenced other martial arts throughout both Asia and the West. An exhaustive review of Indian martial arts spanning centuries can be read on Wikipedia which showcases the rich and varied history of these arts, but the contemporary practice of Indian martial arts can be summarized in a single paragraph.

British colonial rule during the 19th century is considered to have had an extremely negative impact on the martial traditions of India as modernization of the military led to abandonment of many traditions. In response to a number of attempted revolts by the Paika warrior class against British rule the practice of many martial arts such as Kalaripayattu and Silambam were banned in the early part of the 19th century, and wouldn’t be practiced again widely until the early part of the 20th century in a highly diluted form. Today the practice of these arts are primarily for purposes of choreographed demonstrations to amuse spectators at cultural events and they have lost much of their martial applications.

It is worth noting that Indian club swinging developed as a means of muscular conditioning for Indian martial arts and was introduced to Europe during British colonial rule over India.

Malaysian martial arts

This covers the martial arts of Thailand, Philippines and Vietnam.

Muay Thai is well known sport of kickboxing from Thailand. Its origins are claimed to date to the 18th century but the modern practice is shaped by reforms made in the 1930s to make it more similar to Western boxing, which had been introduced to Thailand as part of the curriculum of Suan Kulap College in the 1910s along with Judo. There are a variety of fantastical stories attributed to the history of Muay Thai that are seemingly a consequence of nationalist tendencies rather than based on concrete historical evidence.

Nevertheless Muay Thai is one of the most popular martial arts practiced today due to its effectiveness for real combat situations and its techniques are a staple of mixed martial art combat sporting matches.

Escrima, or Arnis, has its origins in combining the historical knife and sword fighting traditions of Polynesian peoples with Spanish military sabre and stickfighting techniques. This style developed during the Spanish Empire’s colonization of the Philippines starting in the 16th century that lasted until 1898.

The art of Kuntao is also still practiced and is believed to originate from Chinese martial art forms.

Vietnamese martial arts are broadly defined as those descending from the martial practices of the Han and those practiced by the Chams. The precise history of the martial arts of Vietnam was largely oral and therefore difficult to trace, and during the French occupation of Vietnam during the Sino-French War the practice of indigenous martial arts was banned. This restriction wouldn’t legally lift until 1963. Today there are several popular martial arts practiced in Vietnam but most cannot be traced further back than a century and are inspired by other arts from China and Japan.

Comparison of these arts to HEMA

Now that we have broadly surveyed the majority of what are considered Eastern martial arts we can finally discuss how they compare to Historical European martial arts.

As explained in the previous section most of the Chinese and Japan arts that survive today were created for reasons other than a strictly martial application and are relatively new martial arts based on more historical martial arts, and whose lineages generally cannot be traced back further than a century. Although this information is not widely known and contradicts the various mythologies many contemporary martial art traditions have devised for themselves this fact is well documented.

In comparison the modern HEMA movement is a reconstruction of martial traditions that existed centuries ago but whose living lineage of masters died out as the weapon systems became antiquated for their time, losing value in the battlefield. The reconstruction efforts do however attempt to practice the arts as closely to their original incarnations as possible and retain the combat focused aspects — a detail which many Eastern martial arts have lost as they transformed into sports or were influenced by political reforms.

The point of explaining this in detail is not to demean or diminish the value and usage of Asian martial arts but rather to clear up common misunderstandings that prevent people from understanding HEMA in its proper context. HEMA is a new movement and the reconstructed martial art traditions are new, but when the whole of history is considered the HEMA movement is just another part of the enormous changes that took place globally to the practice of martial arts during the 20th century. There were movements to sportify historical martial arts and movements to restore lost martial applications to styles that had been diluted after periods of oppression, and these events took place everywhere.

So, when a person compares HEMA to other contemporary martial arts it is important to understand the correct history of these arts it is being compared to. Far too many people today believe “traditional” martial arts from Asia are very old and therefore must be “better” when in actuality “traditional” is a misnomer, sometimes even a deliberate deception in certain instances.

We hope this article has helped you understand the differences of HEMA vs Eastern martial arts. If you have any questions or something you’d like to contribute to the subject, feel free to comment below.

If you’d like to learn more information about historical fencing practices please check out our Learn HEMA page for a guide to learning about the historical weapon that interests you. You can also find more guides we’ve written about other topics at our Helpful Guides page.

You can also join the conversation at our forums or our Facebook Group community.