We’ve noticed that there is a lot of interest in comparing Japanese Kendo to HEMA swordsmanship on the internet, with many discussions taking place about this topic. There are several reasons for this; Kendo is one of the most popular sword-based sports in the world that is internationally practiced.

In this article we will briefly talk about the origins of Kendo, its popularity worldwide and then compare differences it has to HEMA, including showcasing some footage of a match between a practitioner of European long sword and Kendo.

What is Kendo?

Kendo has its origins in the practices of the Jikishin Kage-ryu school of Japanese swordsmanship. During the Shotoku Era (1711–1715) Yamada Heizaemon Mitsunori developed specialized armor after suffering an injury while sparring with wooden swords, and his son Naganuma Shirōzaemon Kunisato further refined this armor and developed a specialized bamboo practice weapon wrapped in a leather sheath for usage as a sword simulator (Bennet, 2015). Later during the late half of the 19th century attempts were made by the government to unify historical Japanese sword arts into a singular practice with regulations such as standardization of the size of the bamboo practice weapon (Bennet, 2015). The transition of swordsmanship into a sport was a result of the efforts of Sakakibara Kenkichi who during this era organized sword contest demonstrations modeled after similar kinds of events in sumo (Bennet, 2015). The Dai Nippon Butoku Kai (“Greater Japan Martial Virtue Society”) was formed in Kyoto in 1895 to develop a systematic and uniform version of martial art practice for military and police usage, and this standardization of a national sword style was developed by piecing together techniques from multiple historical schools which had survived the Meiji Restoration sword hunts and crackdowns on samurai. In 1920 the DNBK labeled sport fencing using its standardization as ‘Kendo’.

Despite common misconceptions Kendo became an international practice long before World War II and was not spread as part of the “karate craze” of the 1980s but instead sport practice of Japanese swordsmanship was brought with Japanese immigrants as they moved to the United States during the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. Schools teaching Japanese swordsmanship had sprung up in the United States as early as the late 1890s and by the 1930s there were over 10,000 Kendo students in California.

As swords had been a standard issue sidearm by the Japanese military and all soldiers had received extensive training in their usage for war, during World War II the American government placed a ban on Kendo, and then during post-war occupation of Japan the American command banned all aspects of military and ultra nationalistic activity, including the practice of martial arts within Japan and this ban lasted for nearly five years. All Japanese citizens were ordered to relinquish to the American military any weapons, including swords. The DNBK was also disbanded.

It would not be until the 1950s that Kendo re-emerged in a new post-war reformed Japan no longer intended to be a martial art with military values, but instead a sport with educational benefits to teach Japanese cultural values to youth. This version of Kendo is different than its pre-war incarnation as it is not intended to prepare a student for usage of a real sword in battle, and this is the contemporary style practiced today.

What Did Pre-War Kendo Look Like?

As mentioned earlier, before the Second World War Kendo was less the sport we know it as today, and more a sort of military training. As such, it was designed to provide its students with the training they would need to win a real fight and best or kill a real foe. Because of this, pre-war Kendo training allowed for more aggressive tactics that aren’t considered proper by modern practitioners. These included leg sweeps, strikes, and grappling. After the end of the war, Kendo was banned in Japan, but was later reintroduced. The new version of Kendo had rules in place that made it into the sport it is today. The shift of Kendo from military training to sport certainly had something to do with demilitarization in Japan after the war, but probably would have happened eventually anyway, as sword combat was nearly non-existent in real battles by that point.

For an idea of what pre-war Kendo was like you can watch this film clip from a French newsreel produced in 1897. The clip shows Kendo fighters engaging in grappling, leg sweeps, and even sparring with a shinai against other kinds of weapons,

Here is yet another clip where some leg sweeps are showcased, starting at around the 2:58 time stamp in the video.

The techniques taught today in contemporary Kendo are based on practical sword (katana) techniques, but modified to work with the shinai and designed to enforce the moral lesson the student is supposed to learn. This emphasis on the moral lessons is a consequence of the post-World War II social reforms the occupying American forces demanded of the Japanese population and government in order to permit martial arts to be taught in Japan, and these restrictions persisted in Japan for many generations even after the occupation period ended in line with the intention of the Peace Clause within Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution.

This means that Kendo as it was practiced pre-World War II is different than it is now practiced post-World War II, and it’s critical for people to understand this history when comparing Kendo to Historical European martial arts. Essentially, Kendo is to historical Japanese sword arts what contemporary Olympic sport fencing is to historical European small sword and sabre arts.

As part of its intention to teach moral values and qualities, Ki-ken-tai-ichi (Unity of spirit, sword and body) is an important concept in Kendo. In order for a Kendo practitioner to score a point they must call out the name of the target they are striking using a ritual that involves a hard stamp on the ground with their lead foot and a suitable amount of spirited shouting. If they fail to perform this ritual perfectly no points will be awarded to the Kendo fencer even if their strike succeeds at hitting their opponent.

Comparing Kendo to HEMA

Unlike Kendo which is a contemporary sportified version of historical Japanese swordsmanship, HEMA is an umbrella term for historical European martial art styles of fighting and covers many different types of weapons and even unarmed combat.

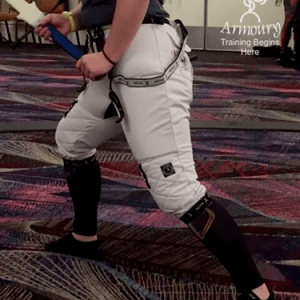

In specifically comparing sword arts, HEMA styles utilize nylon or steel training weapons designed to simulate the characteristics of a real sword of the type the style uses, be it a long sword, rapier, sabre or backsword. HEMA students can even study the use of the great sword (montante).

By contrast Kendo uses a sword simulator called a shinai made from bamboo. Points are earned in a Kendo match when the fencer successfully strikes one of four target areas; wrist, head, body and throat. However each target can only be attacked by specific strikes which must fall in line with one of nine fundamental techniques.

Kendo is highly ritualized in all of its movements and great emphasis is placed on students adhering to these rituals even if they serve no practical purpose for combat. In comparison the arts practiced by HEMA students do not contain such rituals and are focused on fighting as efficiently as possible using the weapons.

This is not to suggest that Kendo teaches no “real swordsmanship” at all. As it is based on historical Japanese swordsmanship it does teach the fundementals of two handed sword combat and a Kendo practitioner can effectively hold their own in sporting matches against a disciple of HEMA-based long sword styles, so long as they are not expected to engage in any grappling. As an example of this the video embedded below shows a match between HEMA practitioner Phil Swift and Kendoist Wilson Humphries.

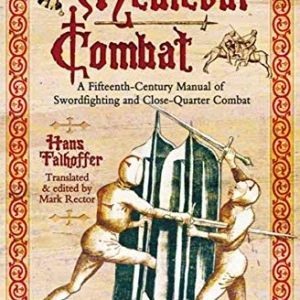

Kendo is an excellent and entertaining contemporary sport that teaches skills that are applicable to sword fighting but its purpose is not to teach accurate historical swordsmanship. In this way it is very different than what is practiced in HEMA. The goal of HEMA students is to be as accurate as possible to historical swordsmanship based on surviving source material from the period in which these weapons were used.

Is there a version of HEMA for Japanese sword martial arts arts?

Yes, as historical research has progressed there are people today seeking to recreate the historical sword arts of Japan. They accept that some of the contemporary schools in Japan teaching sword arts claiming to be ‘traditional’ or Koryū bujutsu are actually heavily modified forms of their original incarnations as a result of social reforms from both the Meiji Restoration and the post-World War II era stamping out many lineages of direct transmission of historical Japanese martial arts. This means that some of the contemporary schools claiming long ancient lineages are fraudulent in nature. An example of a well known fraud is the Bujinkan Organization formed in 1978 by Masaaki Hatsumi, and in the English speaking world Stephen K. Hayes, an early student of Hatsumi, is famous for his various appearances on television shows claiming to demonstrate “ninjutsu”.

Today there is a small movement of Japanese martial artists who study older treatises and historical records, especially of the Nippon Butoku Kai, seeking to reconstruct the original versions of these arts. Some of these people employ methods similar to HEMA martial artists, including using protective gear designed originally for HEMA.

Similar movements to reconstruct historical arts are also taking place in the Middle East and in China.

In Summary

We hope this article has helped you understand the differences of HEMA vs Kendo. If you have any questions or something you’d like to contribute to the subject, feel free to comment below.

Some additional articles featured on our website are listed below that you may be interested in that are related to Japanese martial arts and HEMA.

If you’d like to learn more information about historical fencing practices please check out our Learn HEMA page for a guide to learning about the historical weapon that interests you. You can also find more guides we’ve written about other topics at our Helpful Guides page. You can also join the conversation at our forums or our Facebook Group community.

Partial Bibliography

Bennet, Alexander., 2015. Kendo: Culture of the Sword. University of California Press. pp. 74 -95.

Schmidt, Richard., 1982. The Historical Development of Kendo in the United States. [Online] Available at: https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/budo1968/14/3/14_1/_pdf

[Accessed 6 June 2020].

One Response

It’s a bit too superficial to me, but you saved the main point. Kendo is not about historical correctness, but very philosophical. Calling a do a sport is a bit mean. Although kendo can be done as a sport too.