It can surprise people to discover there are martial artists today who study the usage of historical swordsmanship weapons when fencing instead of the epee and foil. There are people who practice everything from how to fight with a 14th century two handed sword to those who practice 18th century cavalry charges with military sabres. These types of fencers are called Historical European martial artists.

The alternative terms Western martial arts (WMA) and historical European swordsmanship (HES) are also sometimes used, with WMA being another more broad umbrella term and HES used specifically to talk about sword based fighting traditions. In general the majority of HEMA schools focus on the study of two-handed sword based fighting systems that originated in the 14th to 16th centuries of what is today Italy and Germany, but there are also many clubs that cater to those who wish to study the usage of rapiers as taught by Spanish, Italian and German masters, the smallsword and the military sabre. Fighting with a sword and buckler is also popular, and people are even reproducing how to fence using a huge great sword (sometimes called a zweihander or montante).

More broadly HEMA can also mean unarmed fighting styles of folk grappling / wrestling traditions, and even niche eclectic martial arts such as Baritsu.

Historical European martial arts is broadly defined as the study of martial arts that existed pre-20th century Europe. So it covers martial arts that were developed at least a century ago such as military sabre practices but it also covers martial arts practiced by Europeans who lived as far back as the Renaissance and late Middle Ages. Most practitioners study a sword based art as the sword was a very common weapon for civilian and military usage but not all Historical European martial arts are exclusively centered around swordsmanship; the study of everything from how to use a poleaxe to how to fire a musket can be considered within the domain of Historical European martial arts.

As the whole phrase is a mouthful to say the acronym HEMA is most commonly used by practitioners when referring to this discipline, although in other languages another acronym is sometimes used (for example in French it can be labeled d’Arts Martiaux Historiques Européens, or AMHE). HEMA is generally an umbrella term for dozens of traditions of historical martial arts that developed and were practiced by European peoples.

How did Historical European martial arts become revived?

The history of the Modern HEMA Movement is a complicated subject worthy of its own article, but in a general summary, surviving copies of records from teachers of older traditions were re-discovered in museum and university collections by people interested in military history and efforts were made to reconstruct these arts. Most of this development has taken place over the past thirty years.

Are there differences between HEMA and sport fencing?

Yes, and we have an article on our site dedicated to discussing this topic in greater detail, Modern Olympic Fencing Vs. HEMA.

The short version is that contemporary sport fencing uses weapon simulators that are less historically accurate than the types of training weapons used in HEMA, and the rules for tournament matches are not designed to simulate a real sword fight. HEMA is more focused on the latter than sport fencing is.

Types of interpretations in reconstructing historical European martial arts

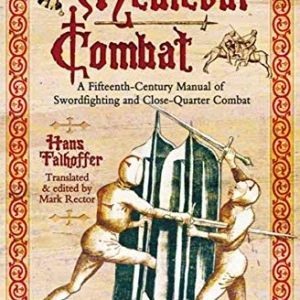

HEMA as a movement is focused on studying source based interpretations; that is, martial arts whose techniques and theories for combat have been recorded in some kind of documentation such as a manuscript, or fechtbuch (fighting book).

There are two basic camps when it comes to how to approach the reconstruction of historical fencing and both camps offer a different answer to the question, “Is historical fencing the revival of historical fencing systems or is it the revival of the use of historical swords for fencing?”

These questions are related but not the same. So there has developed two types of historical fencing interpretations of source material, with most historical fencers falling into one of these two camps,

- Canonical interpretations

- Applied interpretations

Canonical interpretations are those who try to practice only that which is demonstrated by a particular source manuscript. These individuals try to make their interpretations strictly follow the textual instructions and illustrations as closely as possible with no deviations at all. Canonical practitioners will generally avoid mixing material from multiple source manuscripts together and only practice the system describing the manuscript they are studying.

Generally speaking those who approach historical fencing with canonical interpretations are pursuing the study of historical fencing as an academic interest, a form of historical re-enactment or role play designed to further their scholarly study of history and may be less interested in the competitive sporting aspects of the historical fencing movement.

Applied interpretations are those who apply the principles, tactics and mechanics described in the source material to create a system that may be similar to that described in the source material but does not attempt to mirror it exactly. Instead the focus is on developing an effective system of fencing with the historical weapons the sources describe. Applied practitioners will often splice in so-called ‘frog DNA’ (a term in reference to the film Jurassic Park) to create these systems, using information from multiple source manuscripts and even other martial arts. They might even apply ideas borrowed from modern sports science to their interpretations.

Generally speaking those who approach historical fencing from an applied interpretation may be less interested in the study of historical fencing as an academic interest and are instead more interested in the athletic exercise value of historical fencing, often approaching it more as a competitive sport. This however should not suggest applied interpretations provides less historical value than canonical interpretations, as there are certain challenges with canonical interpretations that can frustrate efforts to reproduce the original arts that justify applied interpretations even by those who are more interested in the academic aspects of HEMA.

There are some individuals who have both an academic and athletics interest in historical fencing, and these individuals tend to practice an applied interpretation as canonical interpreters often avoid tournaments and other forms of competitions, sometimes because they find it difficult to use their interpretation in a competitive setting. This is because the source manuscripts often are missing key information necessary for applying the techniques illustrated in the manuscripts, or the text may simply be mistaken. Canonical practitioners sometimes have a habit of treating the source manuscripts as sacred documents and reject the viewpoint that the manuscripts were not intended to be the sole source of instruction for these systems, and could even be reproductions based on the original source treatise. They may also ignore or refuse to acknowledge that these reproductions possess clerical errors in them introduced by the copier who was not familiar with the systems the original manuscripts described.

As an example, nearly every illustration featured in manuscripts from the 15th and 16th century shows a sword with the flat of its blade facing the reader of the manuscript even while performing a parry, instead of the parry having a strong edge alignment in relation to their opponent’s weapon. Subsequently applied interpretation practitioners acknowledge these illustrations lack correct perspective to show edge alignment, and often mistakenly show the flat of the blade to the reader even when the technique is not optimally performed that way. This means at the least they cannot practice the art precisely as the illustrations demonstrate.

As an example of these kind of errors, this illustration from the the MS Ludwig XV 13 version of Fior di Battaglia (“The Flower of Battle” shows incorrect edge alignment for a crossing of blades; in order for this play to work correctly the cross guards should be pointed at the reader with the edges of both swords cutting into one another.

This is not to say that applied interpretations are always the best versions; sometimes deviating too far from the canonical approach can lead to other kinds of errors, too. As the primary goal of the HEMA community is to reconstruct historical martial arts to be as close as possible to their original incarnations it is necessary to be canonical in at least a general sense. Still the usage of applied interpretations often leads to differences of opinion and this results in different teachers often teaching a separate interpretation of the source material. Some of the most heated discussions within the HEMA community can be about these contrasting opinions.

In Summary

We hope this article has been useful to explaining what Historical European martial arts are. If you have any questions or something you’d like to contribute feel free to comment below.

If you’d like to learn more information about historical fencing practices please check out our Learn HEMA page for a guide to learning about the historical weapon that interests you. You can also find more guides we’ve written about other topics at our Helpful Guides page.