Path of the Long Sword

I am the Sword, deadly against all weapons. Neither lance, nor pole-axe, nor dagger can prevail against me.

Whoever stands against me I will crush. I am of royal blood. I dispense justice, advance the cause of good and destroy evil. To those who learn my crossings I’ll grant great fame and renown in the art of fighting.-FIORE DEI LIBERI, 14TH CENTURY IMPERIAL FREE KNIGHT OF THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE AND AUTHOR OF FIOR DI BATTAGLIA, FLOS DUELLATORUM

You should learn that there is nothing about the sword that has been invented for without reason and that a fencer should make use of the point, of both edges, the hilt and the pommel. Each of these has its own special methods in the art of fencing.

UNKNOWN FENCING MASTER, CODEX DÖBRINGER C.1389

HEMA Italian Long Sword

This branch of HEMA study is predominantly focused around The Flower of Battle (Fior di Battaglia, Flos Duellatorum) manuscripts attributed to Fiore dei Liberi ( born ca. 1350; died after 1409), a 14th century imperial knight of the Holy Roman Empire.

The treatises of Fiore’s work are among the oldest surviving fencing manuals to have survived to the present day. Four illuminated manuscript copies attributed to him survive, and there are records of at least two others whose current locations are unknown. The four known manuscripts are designated as Ms. M.383, Ms. Ludwig XV 13, Pisani Dossi Ms. and the Mss. Latin 11269. The two currently lost manuscripts are Codices LXXXIV (Ms. 84) and Codex CX (Ms. 110).

The Ms. Ludwig XV 13 is also referred to as ‘the Getty’ and is considered to be the most complete of all the treatises, though there are some sections appearing in the other copies which do not appear in the Getty. An English translated version of the Latin and the Ludwig can be purchased below.

- The Flower of Battle : MS M 383 Michael Chidester Translation

- The Flower of Battle: MS Latin 11269

- The Flower of Battle: MS Ludwig XV13

Students of Fiore’s source material often refer to their fencing style as L’arte d’Armizare (“the Art of Arms”), which is the name Fiore attributed to his style. Fiore’s manuscripts also includes sections on unarmed combat, dagger, spear, pole-axe, fighting in heavy armor and on horseback. Among the historical fencing community the term ‘Armizare’ is used as a shorthand for this style of long sword fighting.

For more information about Fiore de Liberi’s life and impact on HEMA you can read our longer essay about him by clicking here.

There is another Italian author for HEMA long sword techniques whose writings are also often studied, with their material typically incorporated or combined with material from Fiore.

Philippo di Vadi produced his treatise De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi (“On the Art of Swordsmanship”, MS Vitt. Em. 1324) some time between 1482 and 1487. Vadi’s work covers some of the same material as Fiore’s earlier work but his manuscript contains some differences, such as in his footwork and several original techniques. It appears to be an attempt to update Fiore’s work.

Worth mentioning is that one of the guard positions demonstrated by Vadi but not by Fiore is the posta de falcone which was mis-translated as ‘Guard of the Hawk’ in the film Kingdom of Heaven (2005). The guard also appears in German traditions as vom Dach or Oberhut. Just a little bit of trivia for you.

You can purchase an English translated copy of Vadi’s treatise below.

- The Art of Sword Fighting in Earnest: Philippo Vadi’s De Arte Gladiatoria Dimicandi

Learning Italian long sword fighting

The most direct way to learn is by reading Fiore’s manuscripts. If you do not speak medieval Italian or Latin you will need to read a translation. There are also authors who have provided additional instruction in their own books based on their interpretations of the source manuscript which are helpful for understanding as the source manuscripts themselves have limited text instruction so understanding the original intent and context can sometimes be difficult. Some helpful books are listed below.

- The Beginner’s Guide to the Long Sword: European Martial Arts Weaponry Techniques

- From Medieval Manuscript to Modern Practice: The Longsword Techniques of Fiore dei Liberi

- Fiore Dei Liberi’s Armizare: The Chivalric Martial Arts System of Il Fior Di Battaglia

- The Swordsman’s Companion

- Advanced Longsword: Form and Function (Mastering the Art of Arms Book 3)

- The Medieval Longsword (Mastering the Art of Arms Book 2)

- Complete Works Fiore Dei Liberi Vol 3: Florius de Arte Luctandi

- Complete Works Fiore Dei Liberi Vol 1: Historical Overview and the Getty Manuscript

For more biographical information about the masters studied by Italian long sword fencers, see the following Wiktenauer page links:

Learning Italian long sword fighting online

HEMA German Long Sword

Here begins Master Lichtenauer’s art of fighting with the sword, on foot and on horseback, bare and in armour. And before all things and matters, you should perceive and know that there is only one art of the sword. And this art may have been invented and conceived some hundreds of years ago. And this art is the base and core of all arts of fencing. And Master Lichtenauer possessed and mastered this art wholly, completely and accurately. Not that he had invented and conceived it himself, as it is written before. But he has traveled and searched many lands because of this justified and true art which he wanted to learn and know. And this art is serious, complete and justified.

ANONYMOUS AUTHOR, POL HAUSBUCH (MS 3227A)

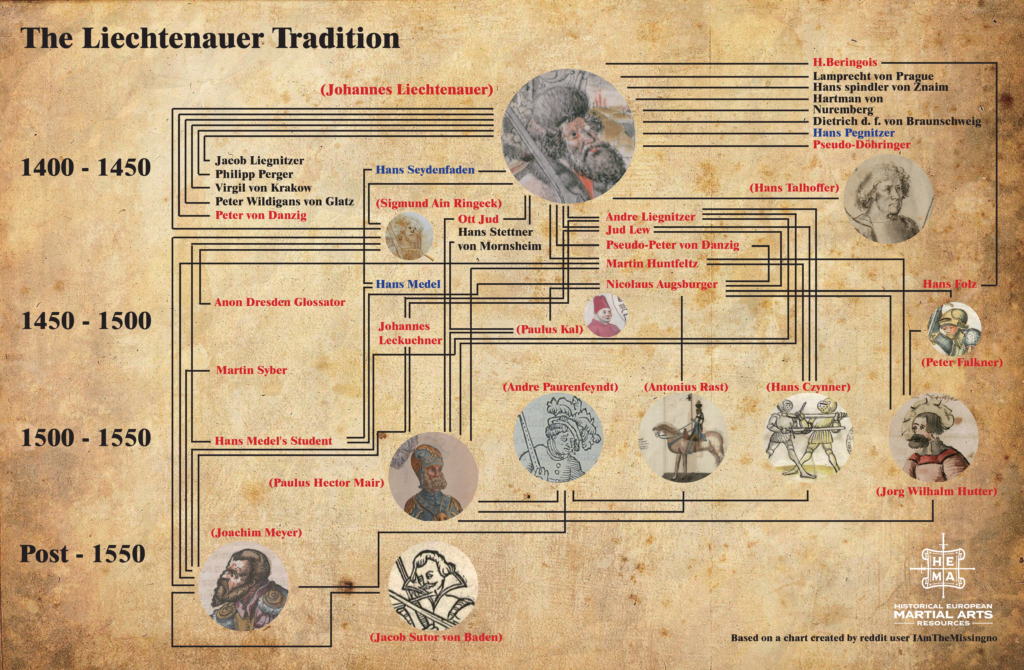

The ‘German long sword’ systems are also referred to in HEMA as the ‘Liechtenauer tradition’ for Johannes Liechtenauer, a German fencing master who lived sometime in the 14th or 15th century. Liechtenauer is attributed as having created what is referred to as the ‘Recital’ (Zettel), a series of cryptic instructions for how to use a variety of weapons appearing in the form of a long poem. The poem is designed to prevent those who do not understand the true meaning of its words to be able to understand the instructions, and also serves as a kind of mnemonic device intended to assist a fencer in remembering the plays of the tradition.

The Liechtenauer tradition is often referred to by modern day HEMA athletes as ‘KdF’ for Kunst des Fechtens( German: The Art of Fencing) and is thought to be associated with the Brotherhood of Saint Mark (Marxbrüder), a fencing guild that enjoyed a state-sanctioned near total monopoly on the teaching of fencing in the Holy Roman Empire from 1487 until 1570.

Many of the earliest mentions of the Recital that survive are not illustrated and difficult to understand. It was not until the re-discovery of illustrated Fechtbücher (“Fight books”) describing this tradition that modern day HEMAist began to study it in earnest. At present it is the Liechtenauer tradition that is the most commonly studied long sword techniques in the HEMA community, primarily due to a perception that certain Liechtenauer sources are easier to understand and there are more sources for it than exist for Italian. The most popular wiki site for archiving historical information pertaining to HEMA is Wiktenauer, which is named after the Liechtenauer tradition and gives an idea of its popularity.

(Note: While the Liechtenauer tradition was not the only German long sword tradition in its day and there do exist other manuscripts such as the Codex Wallerstein (Cod. I.6.4º.2) which showcase a different tradition, when a modern day HEMA fencer talks about “German long sword” they are nearly always referring to the Liechtenauer tradition. So we’ll talk about other German traditions later in this page.

Please further note there are many HEMA treatises involved in the Liechtenauer tradition that all generally cover the same stances, guards, techniques and so on. In order to stay focused we’re only discussing a few of them to give a general timeline of this tradition and the material available for study.)

As there are several masters who produced useful source material in this tradition we will talk about each one in as best of chronological order as can be known today.

As stated in the first paragraph, the first sources we have are the Recitals attributed to Johannes Liechtenauer. While no copies of any treatise attributed to him are currently known to exist, the currently believed earliest mention of his Recital is contained in The Pol Hausbuch (MS 3227a) which includes some details about his life. While the precise date for these entries in the commonbook are not known it is commonly believed to have been made sometime between 1389 and 1494, though this isn’t a precisely correct estimation either.

We feel it is useful to discuss why the wide date range on the Pol Hausbuch creation as there is a lot of confusion among many HEMA practitioners surrounding the date. It is actually possible this source may not be the earliest mention of Johannes Liechtenauer. The source was even once erroneously credited by some HEMA practitioners as having been written by Hans Döbringer, sometimes called ‘Hanko Döbringer’s Fechtbuch by these fencers, who also claimed it was the earliest long sword treatise.

The issue with that claim is there is no proof that the treatises were added to the book in that precise year and all other surviving mentions of the Recital appearing in other books imply a much later date somewhere around the mid 15th century. There isn’t even any proof the astrological calendar was added in 1389 and may have just been copied from another source. Given the other entries in the commonbook this is likely to be the case. The only date known for sure is that it entered the ownership of Nicolaus Pol some time after 1494, who likely purchased it for its alchemy and astrological information given his profession.

This leads us to the next topic that many people are confused about. 1494 is not the date he acquired the book but rather the date which Nicolaus Pol received his medical degree. He apparently decided to immortalize himself in history by marking every book he owned (estimated at 1,394 volumes) with Nicolaus Pol, doctor, 1494. This means the precise date that Nicolaus Pol obtained the Pol Hausbuch is unknowable; we have no information on when he bought it. This means the Pol Hausbuch could have been created any time up until Pol’s death in 1532!

Another source attributed to be an early reference to Liechtenauer is Codex 3227a (also known as Hs. 3227a, GNM 3227a, Nürnberger Handschrift GNM 3227a). This is another commonbook once owned by Pol and marked in a similar way. As with the Pol Hausbuch there are people who use an included calendar from 1390–1495 as evidence for it having been written sometime in 1390 but again, there is no proof of this either.

- “…eyn Grunt und Kern aller Künsten des Fechtens”: The Long Sword Gloss of GNM Manuscript 3227a

The first illustrated Fechtbücher in Johannes Liechtenauer’s tradition (that we know of) was produced by Hans Talhoffer some time in 1448. We know Talhoffer was alive in 1433 because secondary sources say he represented Johann II von Reisberg, archbishop of Salzburg, before the Vehmic court. This illustrated book is known as the MS Chart.A.558 and it is thought to have been his personal journal, but may have also served as a visual aid for his students. Some time between 1446 and 1459 Talhoffer created what is referred to as the Königsegg Treatise (MS XIX.17-3 ), believed to be created for Luithold von Königsegg with more detailed instruction. In 1459 Talhoffer created a third known work, which is known as MS Thott.290.2º and appears to be another personal book. Talhoffer’s final work is known as the Württemberg Treatise (Codex Icon 394a), produced for Eberhardt I von Württemberg as explained on its dedication page. This last manual provides the most amount of unarmed long sword plays of any of the manuscripts Talhoffer produced.

- Medieval Combat in Colour: Hans Talhoffer’s Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat from 1467

- Medieval Combat: A Fifteenth-Century Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat

Some time before 1452 (the precise date is currently unknown) some manuscripts were produced in the Liechtenauer tradition which at present have uncertain authorship. One of these is a gloss that was written by an anonymous writer who past scholars once mistakenly attributed to be Peter von Danzig and is now referred to as ‘Pseudo-Peter von Danzig‘. The gloss was popular and influenced several later manuscripts in the Liechtenauer tradition. One of the copies of this gloss is sometimes referred to as the Jud Lew gloss by some HEMA practitioners for additional information that accompanied it which is attributed to Jud Lew, which is believed to itself be a pseudonym for a fencing master in the Liechtenauer tradition.

- Ringeck Danzig Lew: Long Sword

Paulus Kal produced several manuscripts believed to be written sometime between 1460 and 1514 which are illustrations of Liechtenauer’s Recital and he included among the many weapon forms plays for the long sword. It is here that we gain the list of the Fellowship of Liechtenauer (Geselschaft Liechtenauers), a group of seventeen masters who are attributed by Paulus Kal as students of Liechtenauer’s tradition. It is speculated by those who believe the Liechtenauer tradition is older than the 15th century that the list is of ‘dead masters’ but there is no evidence for this belief, and it may just be a list of contemporary teachers or even a list of men who were part of the same military company.

We know few pieces of Paulus Kal’s life but what is known is that in 1449 he served Louis IV of the House of Wittelsbach, Count Palatine of the Rhine. In 1448, while in the count’s service he participated in the defense Nuremberg, commanding a unit of wheel cannons below the gates. The Nuremberg Council notes from 17 March 1449 mention that he had broken the peace of the city at that time by drawing his weapons.

- In Service of the Duke: The 15th Century Fighting Treatise of Paulus Kal

In 1491 the Codex Speyer (MS M.I.29) was compiled by a scribe named Hans von Speyer. This manuscript is the first to include the works of Martin Syber and Johannes Lecküchner with the Liechtenauer tradition, and it includes the oldest known version of what is known as Syber’s Recital, a version of Liechtenauer’s Recital with unique terminology.

Peter Faulkner was a member of the Brotherhood of Saint Mark (Marxbrüder) guild of fencers that operated in Frankfurt-am-Main. In 1495 he produced the Kunste Zu Ritterlicher Were (MS KK5012) that contains an illustrated version of the long sword Recital. He had also produced a longer version which was known as the Falkner Turnierbuch that was held in the Strasbourg City Archive, and likely destroyed (along with the rest of the Archive) by Prussian bombardment during the Siege of Strasbourg in 1870

- Captain of the Guild: Master Peter Falkner’s Art of Knightly Defense

Sigmund ain Ringeck was also a fencing master of the Liechtenauer tradition, and in the past was erroneously credited as the author of Johan Liechtnawers Fechtbuch geschriebenn (“Johannes Liechtenauer’s Written Fencing Book”; MS Dresden C 487). The book is actually a compilation of treatises and Ringeck’s work is included among them.

The Glasgow Fechtbuch (MS E.1939.65.341) was produced in 1508 and it also is a compilation of several treatises by a number of fencing masters who were part of the Liechtenauer tradition. The book is noteworthy in that it contains the only known version of Sigmund ain Ringeck work that includes his original illustrations.

- Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship: Sigmund Ringeck’s Commentaries on Master Liechtenauer’s Verse

Joachim Meyer is the final author of the Liechtenauer tradition we must talk about, and for a modern HEMA longsword student perhaps the most important. Meyer produced three treatises during his lifetime; the Joachim Meyers Fäktbok (MS A.4º.2) sometime in the 1560s; the Fechtbuch zu Ross und zu Fuss (“Manual on Fencing, on Horse and on Foot”; MS Varia 82) and the Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechtens (“A Thorough Description of the Art of Fencing”). The third treatise was published and printed using woodblocks in 1570 and unlike the previous two manuscripts is a comprehensive treatise where he claimed to teach the entire art of fencing using several weapons, including the long sword. It notably uses terminology that only appears in Syber’s Recital, implying it possessed some degree of endurability that isn’t as obvious when looking at previous Liechtenauer tradition source manuscripts.

Meyer’s work does not use cryptic poetry and is written in plain language. For this reason, of all works in the Liechtenauer tradition it is Meyer’s manuals which are most popularly studied among HEMA practitioners today although he himself was not strictly a student of that tradition. Meyer studied a variety of weapon styles, including that of the Bolognese tradition and he added some of his own original techniques to the system which he taught. As a result of this eclecticism in Meyer’s treatise there are some individuals within HEMA who don’t consider him to be part of the Liechtenauer tradition but he is certainly part of what is considered to be ‘German longsword’.

Overall, Meyer’s material on the long sword is arguably the most popularly studied within HEMA.

- The Illustrated Meyer: A Visual Reference for the 1570 Treatise of Joachim Meyer

- The Art of Combat: A German Martial Arts Treatise of 1570

- The Art of Sword Combat: A 1568 German Treatise on Swordmanship

You can learn more biographical information about these Liechtenauer tradition masters by reading their related Wiki pages,

Learning German long sword fighting

The most direct way to learn is by reading the source manuscripts. If you do not speak medieval German you will need to read a translation, of which several are available. There are also authors who have provided additional instruction based on their interpretations of the source manuscript which are helpful for understanding as the source manuscripts themselves have limited text instruction so understanding the original intent and context can sometimes be difficult. Some helpful books are listed below.

- German Longsword Study Guide

- An Introduction to the Art & Science of Johannes Liechtenauer’s Medieval German Longsword

- Sword Fighting: An Introduction to Handling a Long Sword

- Fighting with the German Longsword

Gladiatoria long sword

At the start of the German (or rather, Liechtenauer) long sword section I mentioned the existence of other Germanic long sword traditions. These are much less common to encounter within the modern HEMA community as there is far less surviving information about them, and so the Liechtenauer tradition is considered to be better to reconstruct a working martial art system from. But in the interest of providing a complete overview of the usage of the long sword among the historical Germanic peoples we’ll talk a little bit about them.

The Codex Wallerstein (Cod. I.6.4º.2) is a German fencing manual created sometime between the 1420s and 1470s. Images of it are frequently shown by documentaries when discussing historical medieval combat but it is not widely researched or studied by the HEMA community. It portrays techniques that are considered by some scholars to be part of the so-called ‘Gladiatoria tradition’ that existed at the same time that the Liechtenauer tradition did, and might represent a more common folk martial art style practiced by all German fencers. Most of the plays are focused around teaching armored combat for judicial duels using various weapons, including the long sword.

The Wallerstein manuscript came in the possession of 16th century aristocrat Paulus Hector Mair in 1556 and was part of the collection of treatises he used for creating his own volumes.

Paulus Hector Mair is worth talking further about. Mair was born to an Augsburg patrician family and served on the city council as an official, eventually obtaining the position of City Treasurer. Thankfully for us Mair had a deep personal interest in fencing and collected numerous treatises and produced extensive notes on many of them. He consolidated many of the treatises in his collection and his notes into a compendium with lavish illustrations titled Opus Amplissimum de Arte Athletica. Three copies of his two volume two survive today; these are referred to as the Dresden (MSS Dresd.C.93 and C.94), the Venice (Codex 10825 and 10826), and the Munich (Cod.icon. 393). Two of the treatises possess unique material not included in the others.

Mair also contributed to the preservation of historical German fencing practices by obtaining the notes of Antonius Rast and organizing them into a treatise which is referred to as Reichsstadt “Schätze” Nr. 82 by scholars. This is a manual believed to be of the so-called Nuremberg tradition, which is named based on the belief the tradition originated in the area of Nuremberg, Germany and is a sub-style of the broader Gladiatoria tradition.

Other manuscripts that are considered part of the Gladiatoria tradition include MS KK5013, MS German Quarto 16, MS U860.F46 1450, the Codex Guelf 78.2 August 2º, and the MS Cl. 23842.

- Gladiatoria Medieval Armoured Combat: The 1450 Fencing Manuscript from New Haven

You can read more information about these masters at their respective Wiktenauer pages,

HEMA English Longsword

The English Long sword tradition is studied in HEMA far less commonly than Italian or German, but is still worth mentioning for the interested student to gain a complete understanding of what material is available.

Additional Manuscript 39564 (also known as the Ledall Roll), Cottonian Titus A XXV, and Harleian MS 3542 are believed to be the some of the only surviving martial arts texts of medieval England. All three were written sometime before 1500. A copy of these manuscripts were translated and published under Paladin Press.

- Lessons on the English Longsword

The most prominent of English fencing masters studied today is George Silver, a 16th century English nobleman and fencing enthusiast. He was likely born in the 1550s or early 1560s.

In 1599 Silver published a treatise entitled Paradoxes of Defence and dedicated it to Robert Devereux, the Earl of Essex. Silver uses “paradox” in the sense of heresy and in this work he speaks against the then wildly popular rapier, detailing what he sees as its inherent flaws as well as those of the foreign fencing styles that emphasize it.

Silver produced a later second volume, Brief Instructions upon My Paradoxes of Defence where he explained his own English fencing style. The manuscript is undated but refers to Great Britain and so must have been written after James I’s introduction of that term in late 1604. Bref Instructions remained unpublished for unknown reasons.

A good overview of Silver’s methods are described in the following books.

- English Swordsmanship: The True Fight of George Silver

- A Scholar’s Guide to the Works of George Silver: Part One

You can learn more biographical information about George Silver at his Wiktenauer page.

Jogo do pau

Jogo do pau ( game of the stick) is a Galician / Portuguese martial art that is an oral tradition. It is believed to have originated as the methods of combat used by medieval peasantry when conscripted as soldiers for battle. The art developed in Galiza and the mountainous regions of continental Portugal, and is probably the oldest continually practiced European martial art descending from the middle ages. A present day teacher of this art, Luis Preto, has made a good deal of effort to spread knowledge and awareness of it and has said he believes it originally contained techniques of swordsmanship in addition to polearm fighting, which he is now reconstructing.

While it is not considered a ‘source based’ martial art in the common sense of how many HEMA practitioners use the term I have included a mention of it here because it is a small sub-section of the overall HEMA movement. It sports some unique footwork not found elsewhere.

- Jogo do pau: Training with the Long Sword DVD

Jogo do pau has a Wikipedia page where you can learn some additional information about it.

Conclusion

There is a lot to learn within HEMA about the usage of the long sword and I realize it can feel overwhelming for a beginner to make tails or heads of where to start. I hope this short guides helps you start down the Path of the Long Sword.

PARTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst Des Langen Schwertes, publisher Peter Lang GmbH, Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften (December 31, 1985) author Hans-Peter Hils ISBN-10: 382048129X ISBN-13: 978-3820481297

Nicolaus Pol Doctor 1494, Cleveland Medical Library Association, 1947.

Catalogue of Medical Works from the Library of Dr. Nicolaus Pol: Born c. 1470, Court Physician to the Emperor Maximilian I, Maggs, 1929.

Die Nürnberger Ratsverlässe, vol 1. Irene Stahl. Degener, 1983.

If you’d like to learn more information about historical fencing practices please check out our Learn HEMA page for a guide to learning about the historical weapon that interests you. You can also find more guides we’ve written about other topics at our Helpful Guides page.

Search

HEMA Resources Newsletter Signup

Signup to our newsletter for updates to new information, articles, products and more related to the exciting world of historical fencing!